ve-header title="Literary Landscapes" background=gh:kent-map/images/landscapes/oasthouses .sticky

Kent is a county of diverse landscapes, from its wild coastal marshes to the uplands of Down and Weald, from the heavily wooded Blean complex above Canterbury to the bleak, windswept chalklands of East Kent.

.cards

Desire Paths

Desire Paths

Desire paths are, in the most literal terms, human-made trails created by erosion. Join Daisy Eleanor walking the desire line as she takes you on an exploration of writing beyond the A to B.

The Kentish Landscape

The Kentish Landscape

Kent is a county of diverse landscapes - inspiring evocations of both rural idyll and horror - from its wild coastal marshes to the uplands of Down and Weald, from the heavily wooded Blean complex above Canterbury to the bleak, windswept chalklands of East Kent.

Kentish place-names and the literary imagination

Kentish place-names and the literary imagination

Place-names (toponyms), whether of towns, villages, individual farms and fields, or of physical features, such as rivers and hills, are imbued with meaning, even when the strict sense (the name’s etymology) might be lost or only partially understood. Names often have regional significance, and even a fictional name, using elements of historic place-names, can conjure a strong sense of place or landscape.

Kentish place-names – ‘Riddley world’

Kentish place-names – ‘Riddley world’

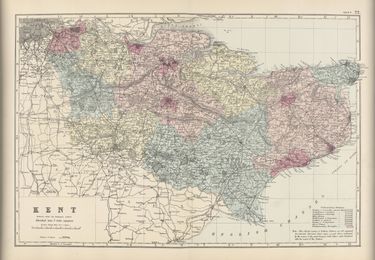

Maps provide a wonderful resource to explore Kent’s placenames and their imaginative potential. Trace, for example, the line of the railway along the River Stour as it carves a gap through the Kent Downs, and recall the announcement as your train pulls out of Ashford - “Calling at Wye, Chilham, Chartham, and Canterbury West” - rhyme and alliteration create a wonderful poesy of place.

Literary Encounters along the River Stour

Literary Encounters along the River Stour

In Roman and medieval times the River Stour was a major transport route, connecting Canterbury with mainland Europe. Its beauty has inspired authors across time.

Scapes and Fringes

Scapes and Fringes

It has become all too fashionable to coin yet another ‘-scape’ (drosscape, playscape, smellscape), however, the root-term ‘landscape’ and some of its derivatives do provide useful means of discussing human and environment interactions and their artistic representations.

The Kentish Chalk

The Kentish Chalk

The chalk dust permeates numerous literary landscapes, including those of Dickens, Belloc, Thomas Ingoldsby (the Rev. Richard Harris Barham), and Jocelyn Brooke.

Chalk Pits, Ash and ‘Stig of the Dump’

Chalk Pits, Ash and ‘Stig of the Dump’

One day Barney tumbles into an old chalk pit that is used as a local dumping ground. Here he encounters a ‘cave boy’ who recycles the materials discarded by others to create his home, tools, and other paraphernalia… This childhood freedom is evoked in Clive King’s classic 1963 children’s book ‘Stig of the Dump’.

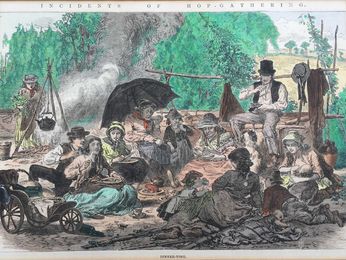

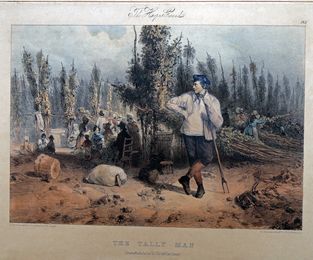

Hop Picking and the Literary Imagination

Hop Picking and the Literary Imagination

To this day the autumn hop picking season provides a potent image of Kent rural life. In the nineteenth and twentieth centuries workhouses were considerably less busy at this time as families and people of all ages went ‘hopping’.

In Darkest London

In Darkest London

Although Margaret Harkness’s novel In Darkest London (1889) primarily takes the reader through the most destitute slums of London, depicting the work of the Salvation Army with a focus on London’s East End, it also includes a “holiday” in Kent.

S.C. Nethersole

S.C. Nethersole

Yonder a meadow down whose length a flock of sheep were folded on successive days; against the horizon line stretched the free downs, owned by none, belonging to all; here sheep might feed, cattle might browse, but no man must fence them in, or if he did the poorest wayfarer might break it down – Wilsam, 1913.

Hop and Fruit Picking in the 20th century

Hop and Fruit Picking in the 20th century

Itinerant hop and fruit pickers are often seen as transient but archetypal characters within the landscapes of Kent. London families who helped with the hop harvest and other ‘travellers’ who followed the seasons and the fruit harvests often feature in the literature on Kent.

Writers of the Romney Marshes

Writers of the Romney Marshes

A number of writers of the Edwardian era and the years between the World Wars chose to depict Romney Marsh in their work. Not least among them was Henry James, who never featured the area in his novels but found the Marsh a very special place.